Words by William Fotheringham

Up to April Fool’s Day, Paris-Roubaix could reasonably be called Schrödinger’s Classic, after the famous quantum mechanics thought experiment. The race was alive in the minds of the organisers ASO, and of teams and riders who had no option but to keep ready for it until told otherwise, and obviously in the hopes of most cycling fans.

However, just as the cat in the thought experiment was essentially waiting for death, most onlookers found it hard to believe that the race would actually take place given the soaring Covid-19 rates in France and the imposition of one lockdown after another.

Finally, we were put out of our misery: the cancellation was announced, and we now have the prospect of “super week” when the World’s will be, improbably, followed by the “Hell of the North.” The weather is bound to be dry.

Of all the Classics, Paris-Roubaix is the one I most love to watch. Clock on soon after the start as I remember doing in 2016, and it can be pretty difficult to leave the room without pressing the live pause button. The 2016 race in particular was that rare beast, a one-day men’s Classic that completely lacked structure of any kind and where most of the best riders seemed to be either tearing up the script or trying to figure out what script there might be if there was one. Tom Boonen’s suicide move 115km out, Peter Sagan’s improbable bunny-hop over a prone Fabian Cancellara, Matt Hayman’s unlikely win: it was all there.

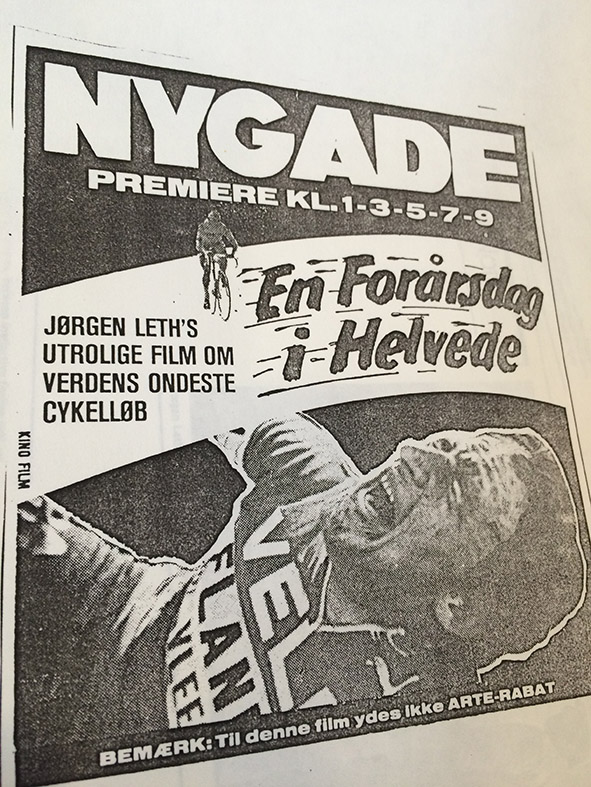

So with neither men’s nor women’s Roubaix on April 11, I’ve got my compensation strategy pretty well worked out: watch a big chunk of 2016, which somehow I’ve never quite managed to delete off the server. And of course, return to Jørgen Leth’s film on the 1976 race, A Sunday in Hell, as I seem to do every year whether or not the actual Roubaix is taking place. When I wrote my “biography” of Leth’s meisterwerk, it was the 2016 race where I scanned the footage at the point where I suddenly got interested in whether you could see much of Leth’s film in the contemporary race. There was a nerdish pleasure in this – as there was in writing much of the book – and you want to see what I actually found out, it’s in the book, which is available here.

I have no issues revisiting A Sunday in Hell for the umpteenth time. Since the book was published in 2018, I’ve been to numerous screenings of the film, and I’m often asked how many times I saw it while I was writing the book. Lost count is the honest answer. But it’s equally honest to say that it never fades. At a time when so much of the culture we consume is instant, and is soon forgotten, there’s a cross-grained pleasure to be taking in knowing a few cultural artefacts really well; films you can watch time after time, books where the pleasure of reading doesn’t fade 10th or 15th time around.

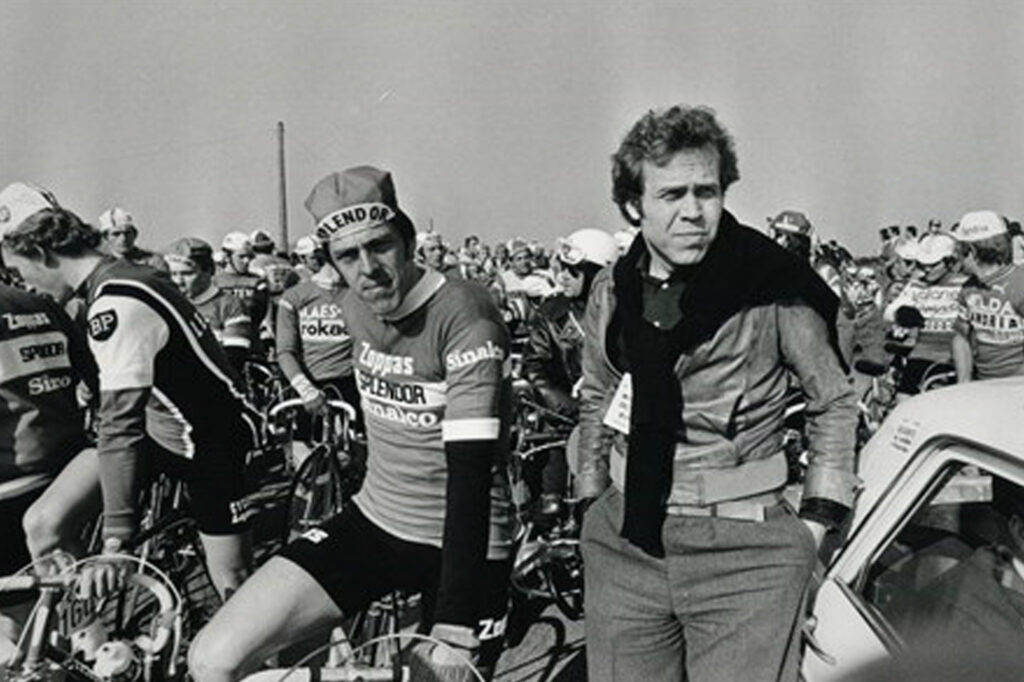

Perhaps it’s just me, but it’s not just about seeing the same old things when I watch A Sunday in Hell for the umpteenth time. Yes, I still buy into the elements that struck me first, all those things that made it, in my view, the best cycling documentary ever made and made it worth a year’s effort to relate how it was made: the weird music, the lingering helicopter shots, the charisma that oozes from Merckx and De Vlaeminck, the close-ups of the bodies bouncing across the cobbles.

There’s the depiction of a bike racing world that seems more real and less neutered than today’s sport, a world where the Flandria team’s stars nip into the hotel bar for a sing-song, where riders hitch lifts to their team vehicles in the feed zone with car-loads of local families who can’t believe their luck, and where mechanics hang improbably off car rooves in the miasma of dust. There are the bizarre bits of humour: the commissaire who mouths platitudes, the strikers who try to stop the race, and the stuff that goes on in the café with hallucinogenic wallpaper. And, of course, there’s Eddy Merckx fixing his saddle height. Time after time.

Photo with thanks to Dan Holmberg.

But like reading a well thumbed novel again, there are always new details that strike on each new viewing: a camera angle here, a bit of cobbles that you hadn’t noticed, or a bike rider you hadn’t spotted before. When there’s so much in one work of art, you can’t take it all in through one single viewing.

There’s more of course. Every year until 2020, on the second Sunday in April, there was always a little thrill, a little tremor running down the backbone. What would it be like? Would it be wet (usually, of course, it was dry)? Would there be the same madness as the years before?

I’ve always found with Paris-Roubaix the intrigue is less about who ends up the winner – I’ve never been bothered whether it was Peter Sagan, Fabian Cancellara or Tom Boonen – than the complete experience: the dust billowing over the fields like gunpowder smoke in a historic battle (or occasionally the mud spattering the camera lenses), the crashes, the punctures, the bizarre twists and turns.

I’m impatient to see all that, to see the greats of women’s cycling in the thick of it all as well – two epics for the price of one – but for the moment, I will switch on the video and fly back 45 years without an immense feeling of loss.

Main photo: The four-man winning break approaches the velodrome in Roubaix. Avenue Roger Salengro, the final approach, has changed little today.