Words by Jeremy Whittle | Photo: Nick Wood

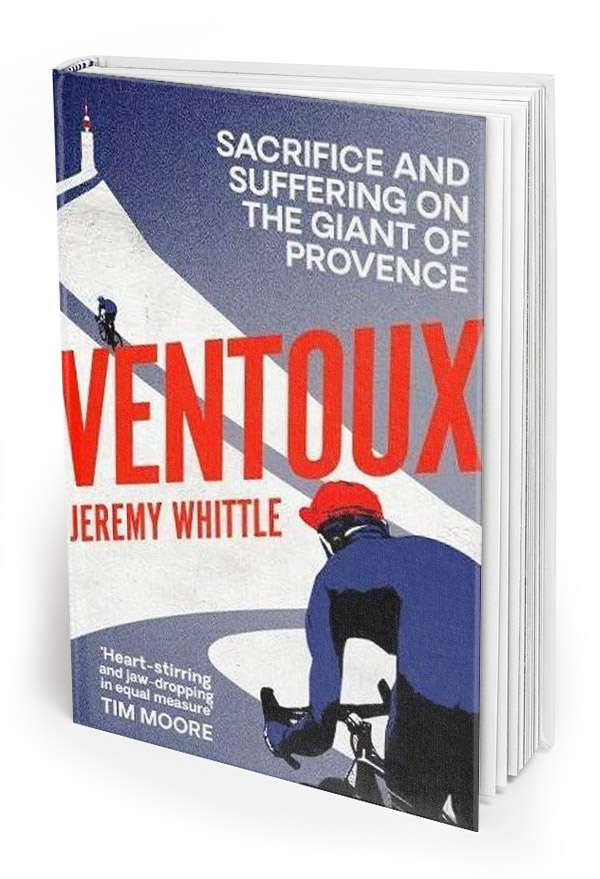

On Wednesday July 7, the Tour de France returns to Mont Ventoux. In his book, ‘Ventoux: sacrifice and suffering on the Giant of Provence,’ La Course En Tete’s Jeremy Whittle traces the beginnings of the post-war fascination with the iconic mountain…

‘As the fans, riders, teams and media discovered just how spectacular Mont Ventoux could be, it became a regular haunt both for the Tour de France and the Dauphine Libere, the early June stage race that traces a tortuous and gruelling route through the French Alps.

The Dauphine, first held in 1947, was — like the Tour — created to fuel newspaper sales, in this case the Grenoble-based Alpine paper, the Dauphine Libere. The race first took the peloton over the Ventoux in 1949, via the banks of snow lining the route up from Malaucene, in a 246 kilometre stage from Gap to Avignon. The race returned frequently throughout the 1950’s, including in 1951, the summer of the Tour’s first visit. It was also included in 1950, 1953, 1955 and 1957, en route to a regular stage finish in Avignon. As a final test for the Tour, the Dauphine became almost essential and for many recent Tour champions — from Miguel Indurain to Lance Armstrong, Chris Froome to Geraint Thomas — that preference continues.

Raphael Geminiani was among the favourites prior to the 1952 Tour. He’d demonstrated his resilience in 1951, and now felt he could challenge for victory. But by the time the race reached the south of France, Faust Coppi had already won the first time trial to Nancy and the summit finishes at Alpe d’Huez and Sestrieres. He led the peloton by almost 25 minutes and the race was effectively decided.

As Coppi stole the show, the Tour organisers, fearful of a loss of interest, doubled the prize money for second place in Paris, hoping to stimulate exciting racing from his closest rivals. Drama had become even more important as, for the first time, the Tour was televised.

That, in itself, was a race against time. Two cameramen shot footage of the race from BMW motorbikes, which, after the stage finish, was rushed to Paris. There, in the Rue Cognac-Jay, legendary broadcaster, playwright and polar explorer, Georges de Caunes – father of Antoine de Caunes of Eurotrash renown — added his commentary over a highlights package.

Boos and whistles had mingled with the cheers that greeted Bobet the previous evening when the Tour arrived in Marseilles. As he listened, stoically, he realised that the Ventoux offered him a chance to suffer for his public…

TVs were not widespread in France in 1952, with only around 50,000 households, mainly in Paris, actually having a set. But already, the power and reach of television was firing the race organisation’s imagination. Now the needs of live television take precedent over all others, including, those even of the riders. By the mid-1950’s the Dauphine Libere and the Tour de France, for any pretenders to success in July, went hand in hand, particularly if both races included Mont Ventoux, as was the case in 1955.

Louison Bobet, once so vulnerable to criticism of his climbing ability, was the dominant force on the Giant that summer. Wearing the world road race champion’s rainbow jersey, Bobet had already proved irresistible in that year’s Dauphine, winning three stages, including a time trial, and finishing second on the stage that climbed the Ventoux.

But a month later the Giant took him, and others, to the brink, in a traumatic stage that revealed the dangers the mountain posed. The drama of the 1955 Tour’s ascent of Ventoux was a prelude of what was to come a little over a decade later.

While the French national team’s Antonin Rolland held the lead as the race arrived in Marseilles, the Ventoux stage was to be pivotal for Bobet, the reigning world road race champion, and Charly Gaul.

The methodic Bobet, after two successive Tour wins, was in danger of being outshone by Gaul, who personified the romance of the lone climber against the fearsome mountain. The French public, despite his success in the Tour, didn’t see Bobet as one of their own.

Boos and whistles had mingled with the cheers that greeted Bobet the previous evening when the Tour arrived in Marseilles. As he listened, stoically, he realised that the Ventoux offered him a chance to suffer for his public, with the panache that the French had come to expect of him.

He and team manager Marcel Bidot hatched the plan for a major attack on the Ventoux, but it was a bigger gamble than his rivals knew at the time. Bobet was fighting the agony of a chronic saddle sore that had become so severe that he rode for long periods out of the saddle in an attempt to relieve the pain.

Radio and newspaper reports of that day’s 198 kilometre stage over the Ventoux describe it as “torrid.” A succession of attacks came and went and by the time the peloton reached Cavaillon, on the banks of the Durance, the field was already fragmented.

Steadily, the temperature rose until by early afternoon, it was nudging 40 degrees. In the villages en route to Bedoin and the foot of the Ventoux, the riders reached into the crowd, grabbing bottles of cold water, or even beer, wherever they could. Some fans even brought hosepipes to the roadside, showering the baking bunch as they pedalled past.

…further down the mountain French rider Jean Mallejac lay unconscious on the verge, “his face the colour of a corpse,” according to one witness. After fifteen desperate minutes lying unconscious at the roadside, eyes wide open and lifeless, the Breton was given oxygen, loaded into an ambulance and finally came around.

But the heat didn’t deter Ferdi Kubler of Switzerland, from attacking. After his double victories in the Ardennes, in Fleche Wallonne and Liege-Bastogne-Liege, and his 1950 Tour win, Kubler had thought he was special, at least until the afternoon in July 1955 when the Ventoux taught him a harsh lesson.

Accounts of what exactly was said vary, particularly between the key protagonists. The spoken words may have been different but there’s no doubt that, as Kubler launched himself at the gradient, Geminiani, sitting on the Swiss rider’s wheel on behalf of Bobet, had a word of warning in his ear.

“Easy Tiger,” (or words to that effect) said ‘Gem’ as he watched the Swiss rider enthusiastically churn the pedals. “The Ventoux’s not like any other climb, you know…”

Kubler scoffed at Gem’s words of wisdom: “Well, Ferdi’s not like any other rider,” he said, with a swagger as he stormed off up the mountain, Geminiani following in his wake.

It was Kubler’s first time racing on Ventoux. He was 36 years old and it was 40 degrees. Even before he got close to the summit he was in a state of delirium, frothing at the mouth, his hook nose drooping low over the handlebars as he weaved back and forth.

He wasn’t the only one swooning in the heatwave.

Some spectators had fainted and further down the mountain French rider Jean Mallejac lay unconscious on the verge, “his face the colour of a corpse,” according to one witness. After fifteen desperate minutes lying unconscious at the roadside, eyes wide open and lifeless, the Breton was given oxygen, loaded into an ambulance and finally came around.

Kubler pressed on, steadily losing both speed and his marbles as he did so. Zig-zagging his way through the final kilometres, he was caught and left behind by Bobet.

Kubler, now riding at a snail’s pace, was followed — at one point on foot — by his team director, Alex Burtin, yelling encouragement.

By the time Kubler hauled himself over the summit, and began the descent, Bobet was already in Malaucene. En route to the finish, Kubler supposedly crashed, twice, then sat in a ditch, swore unintelligibly in German, and frenziedly downed beers in a bar, before setting off again — in the wrong direction.

He finally got to the finish in Avignon 26 minutes behind Bobet, who he’d been hoping to overcome. Bemused by his collapse, he announced his retirement that evening, citing his age and the pain of cycling. “Ferdi has killed himself on the Ventoux,” he said. Perhaps he should have listened to Geminiani after all.

*’Ventoux:sacrifice and suffering on the Giant of Provence,’ is published by Simon and Schuster.