Race analysis by Nick Bull | Main photo by SWpix.com

Fact: prior to Sunday’s race, statistics from the last five editions showed that Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne was the only cobbled classic to average a bigger front group at the finish than Gent-Wevelgem. Fact: thanks to Wout van Aert and Mathieu van der Poel marking each other throughout, a frantic final 90 kilometres and Mads Pedersen’s perfectly-timed bid for glory, this year’s Gent-Wevelgem will go down as one of the best races of the season.

This was Pedersen’s first win in a one-day race since he claimed the rainbow jersey in Harrogate last September. Matteo Trentin and Stefan Küng must be sick of the sight of the Danish rider: second and third in Yorkshire a little over a year ago, they had to settle for third and fifth in Wevelgem this afternoon despite being involved in the action throughout.

Only nine riders remained in contention with two kilometres remaining on Sunday – a far cry from the bunch sprints that decided the winners in 2018 and 2019. Instead of today’s race being determined by finishing speed, tactical awareness, timing and energy expenditure all played a part in Pedersen’s win. Out of the top five finishers, he was arguably the least combative. From the nine riders who were clear approaching the finish, it looked like at least three – van Aert, van der Poel and Küng – were definitely stronger than him. But, as Pedersen said himself, the race came down to a “perfect situation” for him.

84KM TO GO

Trailing a breakaway (one that notably featured Mark Cavendish but ultimately had no impact on the result) by a little over two minutes, INEOS trigger the start of the race proper by splitting the peloton up on the first ascent of the Kemmelberg. Former world champion Michal Kwiatkowski, who was thrust into race-winning contention during Wednesday’s Brabantse Pijl following a huge turn from Luke Rowe, sets about repaying the Welshman on the race’s most famous climb. Van der Poel (in the Dutch champion’s jersey), Pedersen (the sole Trek rider identifiable) and Stefan Küng (on the right-hand side) are all visible in the above still. Van Aert is lurking behind the mini-Groupama train.

Kwiatkowski’s pace, combined with the difficulty of the Kemmelberg, reduces the size of the peloton significantly over the top of the climb. Remarkably, the race barely settles down over the next 20 kilometres. First, crosswinds split the bunch into several groups. Van Aert has a little dig, which is marked closely by Florian Sénéchal (Deceuninck-Quick Step). Then Van der Poel comes to the front of the group on the Hill 63 plugstraat sector; a short-lived eight-rider group (including Matteo Trentin) forms as a result of his increased pace, but Jumbo-Visma quickly shut it down. The day’s breakaway group is then caught by a reduced peloton 64 kilometres out from the line.

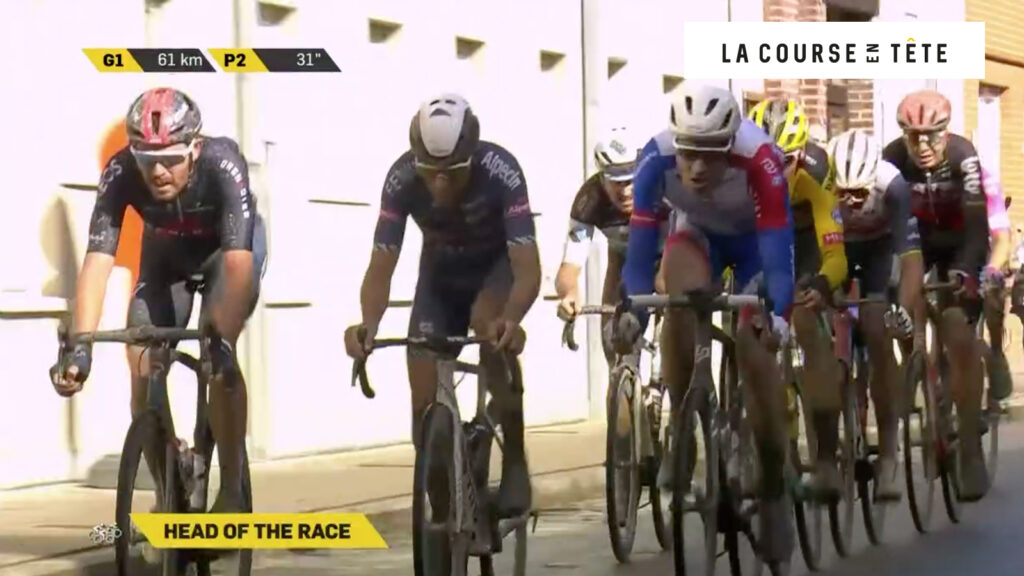

61KM TO GO

After dangling out front for a couple of kilometres, Gianni Vermeersch’s tactically questionable solo attack soon triggers the race’s next action. Rowe, Trentin and Küng are the first to bridge across to the lone leader (and van der Poel’s team-mate), followed by AG2R-La Mondiale’s Alexis Gougeard. Mike Teunissen’s presence in the reduced peloton handily allows Jumbo-Visma to fire the Tour de France stage winner up the road instead of van Aert. Pedersen bridges across with Florian Vermeesch (Lotto Soudal, no relation to Gianni), before 2012 Omloop Het Nieuwsblad victor Sep Vanmarcke (EF Pro Cycling) completes the nine-man group.

In my analysis of Liège-Bastogne-Liège last Sunday, I criticised Julian Alaphilippe for putting his nose in the wind too often too far out from the finish. Highlighting some of the differences in racing between the Ardennes and cobbled Classics, it’s worth noting that of those in this breakaway group, three of them (Pedersen, Trentin and Küng) went on to finish in the top five. Today’s TV broadcast notably showed UAE-Team Emirates DS Allan Peiper telling his riders over the radio not to worry about making big efforts this far out. “You don’t need to save energy – you’ll save energy later by being in front,” he said, referring to the constant fighting for position on the narrow climbs and small roads that feature throughout this race.

At the start of the second Kemmelberg ascent (53 kilometres to go), their advantage was a little over a minute. At the foot of the Baneberg some 13 kilometres later, the gap was just 17 seconds. This significant reduction in time was largely the result of another van Aert attack, this time on the Kemmelberg, which formed a seven-rider chase group. Handily for Deceuninck, Sénéchal and Kasper Asgreen both made it on the right side of this selection. The Belgian team’s hand became even stronger when Yves Lampaert, the two-time Dwars door Vlaandern winner, made it across with 48 kilometres remaining.

34KM TO GO

Küng and Trentin lead the break over the top of the Kemmelberg for the final time (albeit the sole ascent of the climb from its tougher Ossuaire side), before the Swiss time trial specialist goes solo on the descent. Behind, the van Aert chase group bridge across to the remnants of the break.

The chasers sensibly leave Küng hanging out front; his advantage hovers around the 10-second mark for most of his time in the race lead. Van der Poel loses an invaluable tactical option when Vermeersch touches a wheel and crashes heavily with 31 kilometres remaining. The merger of the two groups on the Kemmelberg also swung the race away from Deceuninck a little: Lotto (John Degenkolb and Florian Vermeersch), Jumbo-Visma (van Aert and Teunissen) and EF (Alberto Bettiol and Vanmarcke) also now had two riders in contention. Kung is eventually caught 26 kilometres out from the finish.

15KM TO GO

The next key split begins when Lampaert attacks with 16 kilometres to go. Teunissen sacrifices himself on van Aert’s behalf to neutralise the move. Bettiol immediately counters it; neither Asgreen nor Rowe take up the chase. Eventually Trentin blinks and gives van Aert a generous tow across to the EF rider. As is evident in the above still, Pedersen just about makes it into Degenkolb’s wheel in time. Sénéchal (visible under the L in the LA COURSE logo) is the last man to latch onto the chasers. The way the race splits up here is disastrous for Rowe and Bahrain-McLaren’s Dylan Teuns: they are left in the second group with team-mates of riders who are on the right side of the split. Teuns belatedly tries to bridge across but it’s in vain. He finishes 10th, 1’40” behind Pedersen.

For the next nine kilometres, the leading nine work well together, typically contributing 100-metre turns. Trentin arguably gives a little too much and Bettiol not enough, but they’re in no danger of being caught. For the record, Pedersen’s last turn comes with 5.9 kilometres to go.

The TV cameras picked up Bettiol and Lampaert talking to each other a little under six kilometres out. This removes any surprise from the former’s attack barely 300 metres up the road. Oh, and guess what? Lampaert is able to follow the EF rider’s acceleration owing to Bettiol’s rather generous signal with his head.

Any fears that this year’s Gent Wevelgem would end with a bunch sprint as per the two previous editions were ended here. So, thank you, Alberto, even if this attack was quickly caught. Despite it looking like it was van Aert’s race to lose, the Belgian put out 490 watts when he attacked solo through the town of Menen inside of five kilometres to go. Alert to the danger, van der Poel has to produce a near 500-metre turn to close the gap. This quickly becomes a theme.

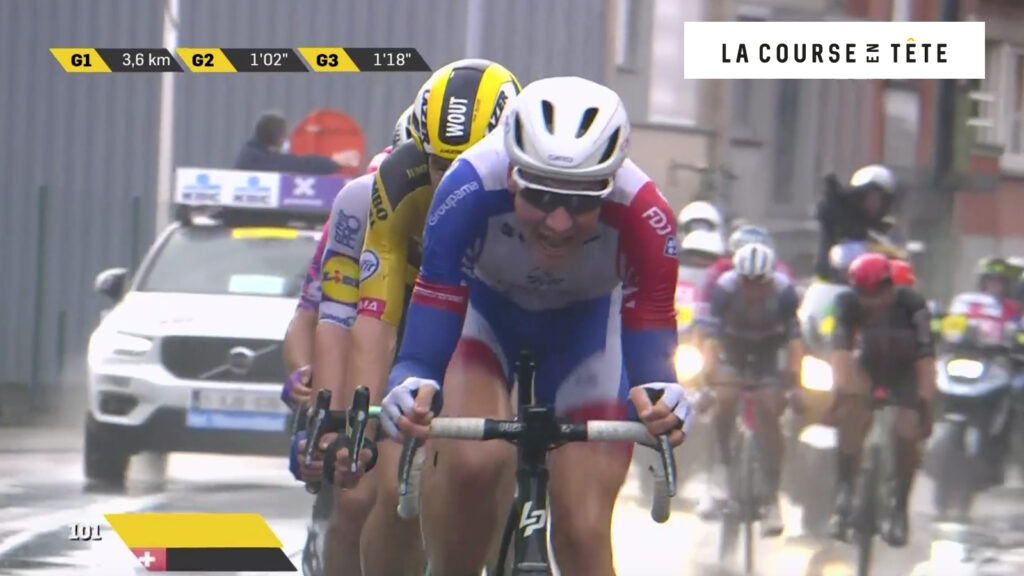

3.6KM TO GO

Küng attacked as soon as van der Poel had led the chasers onto van Aert’s wheel. Impressively, the Jumbo-Visma rider immediately follows the Swiss’s move, followed by Sénéchal and Bettiol. Pedersen begins the chase from behind with a 100-metre turn (the first time he had put his nose in the wind in nearly three-and-a-half kilometres) before putting the responsibility onto van der Poel. The Dutchman makes great inroads into the gap but has to get Trentin to contribute before finishing the job himself.

1.8KM TO GO

Bettiol and Trentin attack almost simultaneously, launching the race-winning move to which only Sénéchal initially responds. Pedersen impressively keeps his cool, watching on from the back of the chase group. The onus to chase is on van Aert, who decides 1,500 metres out from the finish that somebody else should pick it up. However, everybody is too busy watching each other. “I hoped that van der Poel and van Aert would close it down but they didn’t, so I jumped,” said Pedersen. The Trek rider makes it across to the three leaders 950 metres out.

Any hopes of those behind being able to contest for the win ended when van der Poel follows van Aert’s powerful attack under the flamme rouge but sits up once he’s towed the other chasers across. “Apparently he would rather I lose than win himself,” van Aert told Belgian broadcaster Sporza afterwards. “I rode to win the race but I was not given any freedom. It was always the same rider who was in my wheel.”

Pedersen rides a flawless final kilometre. He sits on the back of the lead group, allowing him to recover from his recent effort. The sprint begins some 250 metres from the line, although Bettiol is quickly out of the running. Trentin is narrowly ahead at the 150 metres to go marker but the Italian is quickly overtaken by Pedersen. Sénéchal, who had crashed early on in the day, also comes past him to become just the second Frenchman in the last 23 years to finish on the podium in the race.

Pedersen skipped last month’s world championships in order to prepare for the classics. He would still have had a chance of taking the victory on Sunday even if the front group of nine failed to split in the closing stages, although history suggests the van Aert and van der Poel are faster than him in reduced bunch sprints. The Dane spoke after the race of his desire to prove that last year’s world title-winning ride was not a fluke, but the biggest winner today was arguably Gent-Wevelgem. After two comparatively forgettable editions, the 2020 race felt more like a true cobbled classic – especially when, as van Aert’s sports director Arthur van Dongen accurately said, “the strongest doesn’t always win.”

You can find more of Nick Bull’s race analysis on Twitter

Main photo: SWpix.com / Cor Vos